Maria Clementina Sobieska and the Ursulines of Via Vittoria in Rome

Maria Clementina (Oława, 17 July 1701 – Rome, 18 January 1735), daughter of Prince Jakub and Jadwiga Elisabetta von Pfalz-Neuburg, goddaughter of Pope Clement XI and betrothed to James Stuart, son of the deposed King James II of England, after being kidnapped and imprisoned in Innsbruck for six months, she regained her freedom and married by proxy in Bologna on 9 May 1719[1], immediately afterwards leaving for Rome where she was awaited by the Pope. Clementina arrived in the Eternal City on 15 May[2] and remained there until her death under the protection of Clement XI and his successors.

Maria Clementina's arrival in Rome was eagerly awaited, and preparations began shortly before her arrival in Bologna. The Pope had ordered Monsignors Cervini, Gualtieri and De Giudici to choose six rooms at the Ursuline monastery in Via Vittoria[3], which was built in 1688 thanks to Laura Martinozzi – Duchess of Modena and a fervent Catholic – and her daughter Maria Beatrice d'Este, respectively the grandmother and mother of James III Stuart. The task of furnishing the rooms was entrusted to Monsignor Bartolomeo Massei, chamberlain, and to the chief steward Don Girolamo Colonna Sciarra. To furnish the rooms, they called (in Italian) upon ferrari (carpenters), matarazzari (mattress makers), merchants of tellerie (tablecloths), festaroli (decorators), banderari (flag makers) and various other craftsmen[4]. Furniture and wallpaper were hired; the fabrics used to upholster the rooms and decorate the bed and windows were particularly rich: Cremesi damask, Cremesi ormesino, Cremesi taffeta and gold lace[5]; the patterns had to be non-iconic, mostly floral, in keeping with the fashions of the time; the predominant colour was crimson enriched with gold. As soon as she entered Rome through Porta del Popolo, Maria Clementina was taken to the monastery: «and when she reached the cloister gate, a Most Eminent Person said: Mother Superior,[6] we give you Madama San Giorgio, for that is what she must be called for now»[7]. The welcome was warm. Cardinals, princes, ambassadors and ladies of Rome paid homage to Sobieska by sending her compliments and gifts, which the princess shared with the sisters of the monastery: sweets, citrus fruits, various foods decorated with flowers and ribbons, several cases of wine and a calf adorned with garlands of fresh flowers and ribbons[8].

Maria Clementina lived in the monastery for the next four months, until the wedding was celebrated, with Giacomo in attendance, on 1 September 1719 in Montefiascone[9]. During her stay, the queen-to-be - a young and devout woman - fulfilled all the commitments required by the ceremony[10], before returning to the convent where she was able to enjoy moments of leisure. On 21 June, the birthday of her husband James III was celebrated[11]; again in the convent in Via Vittoria, on Monday 17 July, the birthday of «Clementina Sobieski, Queen of England»[12] was celebrated, «a lunch was given for all and for her under a throne, and all were served by knights and a cantata[13] for three voices was sung, composed especially for the occasion»[14]. At the end of August, Maria Clementina took part in her final engagements, and «at 9 o'clock on Friday morning [1 September], the Queen of England left for Montefiascone to meet her husband, King James»[15].

Maria Clementina's stay with the Ursulines ended with her marriage in Montefiascone, but she always remained close to them. After the wedding, the newlyweds returned to Rome and immediately went to visit the Ursulines, bringing them numerous gifts[16]. This affection was reciprocated by the nuns, who placed a commemorative plaque (fig. 1) in her honour in the sacristy of their church[17] as a sign of gratitude:

CLEMENTINAE SOBIESKI MAGNAE BRITANNIAE | REGINAE | qvod sva divtvrna commoratione praeclarisque | virtvtvm exemplis monasterivm celebrivs redditvm | dignis regali sva liberalitate donariis cvmvlaverit | maria iosepha de middelborg[18] praeses et moniales | grati animi monimentum posvere anno – d – mdccxxxiv[19].

In addition to this plaque, the Ursuline nuns have preserved two patinated plaster busts,[20] one of Sobieska and the other of Clement XII (figs. 2-3).

The two sculptures, characterised by a marked softness in their pictorial modelling, can be attributed to the Florentine Filippo Della Valle,[21] a pupil of Giovan Battista Foggini who, after moving to Rome and joining Camillo Rusconi's workshop, became one of the most prolific sculptors of 18th-century Rome. It seems that he learned the art of stucco from Rusconi himself[22].

While there are numerous well-known painted portraits of the Polish noblewoman, our bust appears to be unique in sculpture. The young Maria Clementina wears a regal dress typical of the Polish nobility: a fur-trimmed cloak, a corset and a shirt embellished with a jewel in the centre. The portrait is both idealised and naturalistic. The curly white wig found in many paintings is absent; her long hair is loose on one side and partly gathered into an elegant chignon. This bust, created with soft lines and a gentle expression, gives us an image of the queen that seems to celebrate her virtues.

The bust of Clement XII, with its schematic and simplified rendering, acts as a counterpart to that of Maria Clementina. It is a youthful portrait of the Pope that can be dated to around 1730. The bust appears to be derived from the terracotta preserved at the Museum voor Schone in Ghent (inv. 1914-DL). This is confirmed both by traces of the technique used and by the conformity in measurements and details. Pope Corsini had particular respect for Maria Clementina. He ordered a solemn funeral for her and wanted her to be buried in St. Peter's Basilica in the Vatican.

A painting recently found at the Ursuline Convent - originally from the monastery in Via Vittoria - shows what the façade of the convent looked like in the mid-19th century (fig. 4). Some renovations were carried out by architects Mauro Fontana and Pietro Camporese in the mid-18th century, but these seem to have mainly affected the cloister[23], so we can imagine that the façade would have looked much the same as it did in Clementina's time. The painting, which is unsigned, has a note on the back explaining that it was a gift from Bianca Lorenzana to her aunt, Sister Maria Nazarena Lorenzana, and is dated 23 October 1860. The painting demonstrates knowledge of the principles of classical landscape painting, albeit rendered in a more simple form. The simple landscape architecture is arranged by a row of trees and small figures in the foreground, sloping gently towards the horizon. The returned architectural structure is still recognisable in this layout today: the entrance door with a triangular pediment is surmounted by an oval window embellished with volutes and crowned, in turn, by a small pediment with a full arch in the centre; Further to the right, we can see the entrance to the church dedicated to Saints Joseph and Ursula, where Maria Clementina used to retreat to pray. The doorway is framed by two tall pilasters that reach the third row of windows, rising above the string course. The doorway's pediment is centred, while the more majestic pediment connecting the pilasters is triangular. Today, we can still see the oval shrine on the corner of Vicolo delle Orsoline, currently without the painting and the crown, which is emphasised and perhaps idealised in our painting. Based on the dedication on the back, we can assume that the painting was painted by the niece of the Ursuline sister. It was not uncommon for the education of young girls at that time to include a painting class. Girls received an education that emphasised the arts considered suitable for their “gender”, such as embroidery, drawing, painting and music, in order to develop grace, refinement and good manners.

After leaving the convent in Via Vittoria, Maria Clementina continued her life in Rome in a turbulent manner, but thanks to her devotion, great modesty and dignity, she won the hearts of the Pope and the Romans and always enjoyed great respect and consideration. The Ursuline nuns suffered greatly from her death, but were able to continue to benefit from James III's visits even after the loss of the queen: «The Lord soon wished to crown her in Paradise, and after a few years she died to the infinite sorrow of all, particularly this Community. His Majesty the King continued to favour visiting twice a year for the monastery's celebrations».[24]

Footnotes

[1] Cf. Platania 2023, p. 90.

[2] Cf. Chracas, no. 291, 20 May 1719, p. 14.

[3] Cf. Platania 2023, p. 91. The former convent is now home to the Accademia di Santa Cecilia, which took possession of it in 1876.

[4] Cf. ASR, Camerale I, b. 2017bis, fascc. 13/7, 13/8.

[5] ASR, Camerale I, b. 2017bis, fasc. 13/7.

[6] Mother Ursule Thérèse Fercamen, Superior from 1704 to 1722. Cf. AGUUR, Ad 9, Supérieures de Via Vittoria, f. n.n.

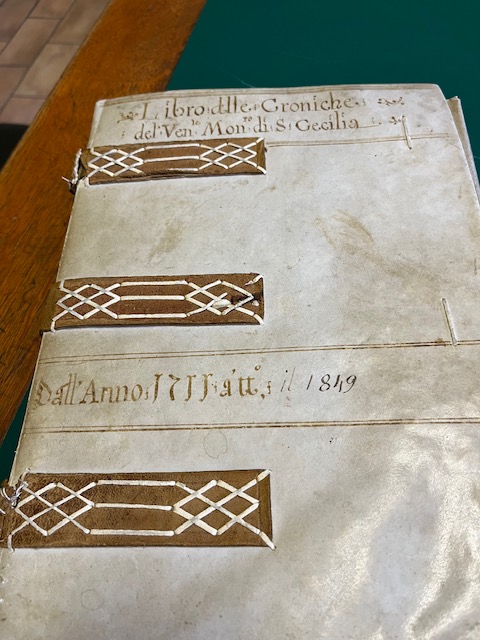

[7]AGUUR, Ad 4, Chroniques Via Vittoria 1688-1847, L’Établissement des Religieuses de Sainte Ursule à Rome l’an 1688, p. 76.

[8] There, pp. 15-16.

[9] On marriage, see Breccola, Ceci 2020 with bibliography.

[10] For a summary of Maria Clementina's commitments, see Lauro 2025, pp. 249–250.

[11] Cf. Chracas, no. 307, 24 June 1719, p. 11.

[12] Chracas, no. 319, 22 July 1719, pp. 23-24.

[13] Cf. Cantata per il giorno natalizio della Sacra Reale Maestà Britannica di Clementina Regina d’Inghilterra […] dedicata a Sua Maestà Britannica da Monsignor Francesco Bianchini Cameriere d’onore di Nostro Signore, Roma 1719.

[14] AGUUR, Ad 4, Chroniques Via Vittoria 1688-1847, L’Établissement des Religieuses de Sainte Ursule à Rome l’an 1688, p. 77.

[15] Cf. Chracas, no. 337, 2 September 1719 p. 24.

[16] AGUUR, Ad 4, Chroniques Via Vittoria 1688-1847, L’Établissement des Religieuses de Sainte Ursule à Rome l’an 1688, p. 77.

[17]The church of St Joseph and St Ursula attached to the convent.

[18] Marie Joseph de Middelborg was the fourth Superior of the monastery, holding office until around 1739. Cfr. AGUUR, Ad 9, Supérieures de Via Vittoria, f. n.n.

[19] ”In the year of our Lord 1734, Mother Superior Maria Giuseppa di Middelborg and the sisters laid a testimony of gratitude in honour of Clementina Sobieski, Queen of England, because with her long stay and glorious examples of virtue she filled the monastery with gifts worthy of her royal generosity, making it more distinguished” (translation by the author). The plaque is now located in a room in the convent of the Province of Italy of the Ursuline Roman Union.

[20] See Petrucci 2025, pp. 387–390 with bibliography. The busts were recently restored by Dr Matilde Migliorini, thanks to the contribution of the Polish National Institute of Cultural Heritage Abroad “Polonika”.

[21]On Filippo della Valle, see the recent monograph by Parisi, 2025.

[22] Parisi 2025, p. 87.

[23] In 1743, the sisters requested a subsidy of 7,000 scudi from Benedict XIV to expand the cloister structure. See ASR, Camerale III, b. 1889, S. Orsola, fascc. 3 and 13.

[24] AGUUR, Ad 4, Chroniques Via Vittoria 1688-1847, L’Établissement des Religieuses de Sainte Ursule à Rome l’an 1688, p. 77.

Bibliography

- Breccola, Ceci 2020

Breccola Giancarlo, Ceci Francesca (a cura di), Il matrimonio di Giacomo III Stuart e Maria Clementina Sobieska: 1 settembre 1719 a 300 anni dalle nozze regali di Montefiascone, atti del convegno (Montefiascone, 30 novembre 2019), Archeoares, Terni 2020. - Cantata 1719

Cantata per il giorno natalizio della Sacra Reale Maestà Britannica di Clementina Regina d’Inghilterra […] dedicata a Sua Maestà Britannica da Monsignor Francesco Bianchini Cameriere d’onore di Nostro Signore, Roma 1719. - Lauro 2025

Lauro Emanuela, Il soggiorno di Maria Clementina Sobieska presso il monastero delle Orsoline di via Vittoria a Roma, in Una Regina polacca in Campidoglio: Maria Casimira e la famiglia reale Sobieski a Roma, catalogo della mostra Roma, Musei Capitolini (11 giugno – 21 settembre 2025), a cura di Francesca Ceci e Jerzy Miziolek, con Francesca De Caprio, «L’ERMA» di BRETSCHNEIDER, Roma-Bristol (USA) 2025, pp. 247-254. - Parisi 2025

Parisi Camilla, Filippo della Valle scultore (1698-1768): la vita, le opere, i contemporanei, Dario Cimorelli Editore, Milano 2025. - Petrucci 2025

Petrucci Francesco, Schede nn. 45-46, in Una Regina polacca in Campidoglio: Maria Casimira e la famiglia reale Sobieski a Roma, catalogo della mostra Roma, Musei Capitolini (11 giugno – 21 settembre 2025), a cura di Francesca Ceci e Jerzy Miziolek, con Francesca De Caprio, «L’ERMA» di BRETSCHNEIDER, Roma-Bristol (USA), pp. 387-390. - Platania 2023

Gaetano Platania, La fuga da Innsbruck a Roma di Maria Klementyna Sobieska Stuart, in From East to West. Women journey in the early modern period to Italy (XVII-XVII centuries), in Eastern European History Review, Special issue, n. 6/2023, edited by Jarosław Pietrzak, Viterbo 2023, pp. 75-102.